Monday, March 28, 2016

Adolf Hitler

1. Waldviertel (the wooded quarter)

2. The peasants there have slav features

3. 1435 Hansen Hydler - deed

4. Jans Hytler

5. Derivative Heidler (Heath or heathen)

Louis Botha

-->

Louis Botha (27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South Africanpolitician who was the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa—the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer War, he would eventually fight to have South Africa become a British Dominion.

Andrew Geddes Bain (5)

Andrew Geddes Bain (baptised 11 June 1797 – 20 October 1864), was a South African geologist, road engineer, palaeontologist and explorer.http://esat.sun.ac.za/index.php/Kaatje_Kekkelbek_or_Life_Among_the_Hottentots

Wrote:

My name is Kaatje Kekkelbek,

I come from Kat Rivier,

Daar’s van water geen gebrek,

But scarce of wine and beer.

Myn A B C at Philip's school

I learnt a kleine beetje,

But left it just as great a fool

As gekke Tante Meitje.

http://esat.sun.ac.za/index.php/Kaatje_Kekkelbek_or_Life_Among_the_Hottentots

REV. DR. PHILIP.

[KAATJE KEKKELBEK enters, playing a Jews Harp.]

My name is Kaatje Kekkelbek,

I come from Katrivier,

Daar is van water geen gebrek,

But scarce of wine and beer.

Myn A B C at Philips school

I learnt a kleine beetje,

But left it just as great a fool

As gekke Tante Mietje.

(Spoken.) Regt dat's amper waar wat ouw' Moses in the Kaap zegt van Dr. Philips zyn school. Hy zegt das ist alles louter flausen en homboggery Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

But a, b, ab, and i, n, in

I dagt met uncle Platje,

Ai'nt half so good as brandewyn

And vette karbonaadje;

So off we set, een hele boel,

Stole a fat cow, and sack's it,

Then to an Engels Setlaars fool

We had ourselves contracted.

(Spoken.) De Engels is een goede soort mens, maar hulle laat hulle te danig vern.... van de Hottentots. Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

His va'rlands scheep was plenty fat,

His brandewyn was sterk ook,

Maar ons hombogged him out of both

For very little werk ook;

And what he would not geef ons took

For Hottentot is vry man -

We stole his fattest ox, en ook

We drunk his vaatjes dry, man

(Spoken.)Ja, jong! jy kan myn g'lo dat ons het die setlaar gehad, en hy denk altoos dat het ander volk is wat zyn goed steel; so een Jan Bull is een domme moer-hond een kleine kind kan hom vern...k! Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

Drie months we daar got bayaan kos

For stealing os en hammel,

For which when I again got los,

I Thank'd for Capt. Campbell.

The Judge come round - his sentence such

As we thought just en even;

"Six month hard work," which means in Dutch

"Zes maanden lekker leven!"

(Spoken.) Regt! se een Boer is een moer slimme ding! Hy was eens net so stom als de Setlaars en Christenmens, maar Hot'nots en Kaffers het hom slim gemaakt! Ja! rasnawel, ons het die dag so lekker sit en karnaatjes eet, dat de vet solangs de bek afloop - maar hier kom de Boer by ons uit met zyn overgehaalde haan en sleep ons heele spul na de tronk. Maar nou trek hy weg, over Grootrivier, die moervreter zeg dat hy niet meer kan klaar kom met de Engelse Gorment! Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

We next took to the Cowie Bush

Found sheep dat was not lost, aye!

But a schelm boer het ons gevang,

And brought us before McCrosty;

Daar was Saartje Zeekoegat en ik,

En ouw Dirk Donderwetter,

Klaas Klauterberg en Diederik Dick,

All sent to the tronk together.

(Spoken.) So een Jud, hy verbeel hom dat hy slim en geleert is, als hy daar zit met zyn witte kop, wat net so lyken als die ding waar de Engelse die vloer mee schoon maak, enzyn mantel en bef net als een predikant; - maar ons Hotnots, will jy g'lo, is bayaan slimmer, ons weet wel wanneer ouw Kekwis rond kom - dan steel ons de meeste, want zyn straf is altoos "Six months hard labour!" maar de kwaai ouw met die rooi bakkies, wat hulle zeg Menzie, die is beetje straf - hy geef ons twee jaren in de bandiet, en laat ons klop so als in ouw Breslaar zyn tyd. Maar de lange speetses van Seur Jan Wyl, daar geef ons niks om! Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

De Tronk, it is een lekker plek

Of t'was not juist so dry,

But soon as I got out again

At Todd's I wet mine eye;

At Vice's house, en Market-square,

I drow'd my melancholies,

And at Barrack Hill found soldiers there

To treat me well at Jollies.

(Spoken.) Rasnavel, jong! jy kan myn g'loo dat die ouw dikke kerel zyn brandewyn lekker is! maskie ouw Pratt zyn ook. Maar ons neem altoos sluk by ouw Todd, als ons uit de tronk kom, dan smaak hy reg lekker! Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

Next morn dy put me in blackhole

For one rix-dollar stealing,

And knocking down a vrouw dat had

Met myn sweat heart some dealing;

But I'll go to the Gov'nor self,

And tell him in plain lingo,

I've as much right to steal and fight

As Kaffir has or Fingo.

(Spoken.) Dats onregt, het is de grootste onregt in de wereld! de teef het myn man afgeronseld, en hulle het my in de blackhole ingesteek! Ik moet gelyk krygen; de Engelse Gorment moet my gelyk geef, anders zal ik toon van daag wat Kaatje Kekkelbek kan doen! Met myn Tol de rol, enz.

Oom Andries Stoffels in England told

(Fine compliments he paid us)

Dat Engels dame was just de same

As ons sweet Hot'not ladies.

When drest up in my voersits pak,

What hearts will then be undone,

Should I but show my face or back (Kaatje here turns round)

Among the beaux of London.

(Spoken.)Regt, jong! I wish toch dat de Mist-in-wary Syety would send me to England to speak de trut net so as Oom Andries en Jan Zatzoe done in Extra Hole, waar al de Engelse come met ope bek om alles in te sluk wat ons Honots vertel. I not want Dr. Flipsy to praat soetjes in myn oor wat I moet say, so hy done met Jan Zatzoe, en ouw Riet do met oom Andries. Kaatje Kekkelbek het zelfs een tong in haar smoel, en is op haar bek niet gevalle. Ik zal vertel hoe dat de Boere en de Setlaars ons hier vern... en verdruk, en dat hulle een Temper Syety hier wil oprigt om ons niet meer btandewyn te laat drink, dan zal ik plenty va'rlands t'wak en dacha kryge om te stop, en brandewyn en halfkroons, want als een mens wil ryk word in England, jy moet maar bayaan kwaad sprek van de Duits volk; - maar hulle zal my niet laat gaan, hulle is bang voor Kaatje Kekkelbek! Maar myn right wil ik hebbe! Ik gaat verd..... na de Gov'neur - Exit Kaatje.

umir.umac.mo/jspui/bitstream/123456789/.../3577_0_Kaatjiepublish.pdf

Jesus Christ (4)

His teachings inspired missionaries who brought education and the written word to South Africahttp://jesuschrist.lds.org/SonOfGod?lang=eng

Jan Christiaan Smuts (3)

Jan Christiaan Smuts He was the only man to sign both of the peace treaties ending the First and Second World Wars.n 2004 Smuts was named by voters in a poll held by the South African Broadcasting Corporation (S.A.B.C.) as one of the top ten Greatest South Africans of all time. The final positions of the top ten were to be decided by a second round of voting but the program was taken off the air owing to political controversy and Nelson Mandela was given the number one spot based on the first round of voting. In the first round, Field Marshal Smuts came ninth.

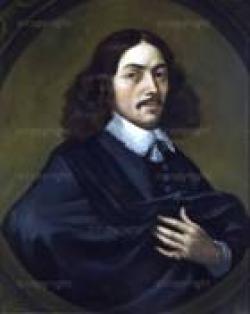

Jan van Riebeeck (1)

Riebeeck, Jan van, and Robert Kirby. The secret letters of Jan van Riebeeck. London, England, UK: Penguin Books 1992; ISBN 978-0-14-017765-7

Collins, Robert O. Central and South African history. Topics in world history. New York, NY, USA: M. Wiener Pub. 1990; ISBN 978-1-55876-017-2.

Hunt, John, and Heather-Ann Campbell. Dutch South Africa: early settlers at the Cape, 1652–1708. Leicester, UK: Matador 2005; ISBN 978-1-904744-95-5.

-->

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch colonial administrator and founder of Cape Town.

-->

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch colonial administrator and founder of Cape Town.

Van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg, a culturally Dutch free state then officially part of the Holy Roman Empire, as the son of a surgeon. He grew up in Schiedam, where he married 19-year-old Maria de la Quellerie on 28 March 1649. She died in Malacca, now part of Malaysia, on 2 November 1664, at the age of 35. The couple had eight or nine children, most of whom did not survive infancy. Their son Abraham van Riebeeck, born at the Cape, later became Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

Joining the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) (Dutch East India Company) in 1639, he served in a number of posts, including that of an assistant surgeon in the Batavia in the East Indies.

He was head of the VOC trading post in Tonkin, Indochina.

In 1643, Riebeeck travelled with Jan van Elseracq to the VOC outpost atDejima in Japan. Seven years later in 1650, he proposed selling hides of South African wild animals to Japan.[4]

In 1651 he volunteered to undertake the command of the initial Dutch settlement in the future South Africa. He landed three ships (Dromedaris;Reijger and Goede Hoop) at the future Cape Town on 6 April 1652 and fortified the site as a way-station for the VOC trade route between the Netherlands and the East Indies. The primary purpose of this way-station was to provide fresh provisions for the VOC fleets sailing between the Dutch Republic and Batavia, as deaths en route were very high. The Walvisch and the Oliphant arrived later in 1652, having had 130 burials at sea.

Van Riebeeck was Commander of the Cape from 1652 to 1662; he was charged with building a fort, with improving the natural anchorage at Table Bay, planting cereals, fruit and vegetables and obtaining livestock from the indigenous Khoi people. In the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden in Cape Town there are a few Wild Almond trees still surviving. The initial fort, named Fort de Goede Hoop ('Fort of Good Hope') was made of mud, clay and timber, and had four corners or bastions. This fort was replaced by the Castle of Good Hope, built between 1666 and 1679 after van Riebeeck had left the Cape.

Van Riebeeck was joined at the Cape by a fellow Culemborger Roelof de Man(1634-1663) who arrived in January 1654 on board the ship Naerden. Roelof came as the colony bookkeeper and was later promoted to second-in-charge.[5]

Van Riebeeck reported the first comet discovered from South Africa, C/1652 Y1, which was spotted on 17 December 1652.

In his time at the Cape, Van Riebeeck oversaw a sustained, systematic effort to establish an impressive range of useful plants in the novel conditions on the Cape Peninsula – in the process changing the natural environment forever. Some of these, including grapes, cereals, ground nuts, potatoes, apples and citrus, had an important and lasting influence on the societies and economies of the region. The daily diary entries kept throughout his time at the Cape (VOC policy) provided the basis for future exploration of the natural environment and its natural resources. Careful reading of his diaries indicate that some of his knowledge was learned from the indigenous peoples inhabiting the region.

References:

- See more at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/arrival-jan-van-riebeeck-cape-6-april-1652#sthash.tTwW5nvU.dpuf

THE STAR - 100 people who made SA (No.1) Dec6 1999

Portrait of Jan van Riebeeck (after original by Dirk Craeij in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), 1972 Source: africamediaonline.com

On 24 December 1651, accompanied by his wife and son, Jan van Riebeeck set off from Texel in The Netherlands for the Cape of Good Hope. Van Riebeeck had signed a contract with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to oversee the setting up of a refreshment station to supply Dutch ships on their way to the East. Sailing on the Dromedaris with two other ships, the Rejiger and De Goede Hoop, Van Riebeeck was accompanied by 82 men and 8 women.

When Van Riebeeck left The Netherlands in 1651, the Council of Policy, a bureaucratic governing structure for the refreshment station, had already been established. On board the Dromedaris Van Riebeeck conducted meetings with his officials – minutes of the meetings of the Council of Policy, dated from December 1651, have been carefully archived.

Charles Bell (1813-1882) painting of Jan van Riebeeck arrives in Table Bay in April 1652www.andrewboraine.com

Land was sighted on 5 April 1652 and the ships docked the next day. Within a week of the arrival of the three ships, work had begun on the Fort of Good Hope. The aim was to establish a refreshment station to supply the crew of the Company's passing trading ships with fresh water, vegetables and fruit, meat and medical assistance. However, the first winter experienced by Van Riebeeck and his crew was extremely harsh, as they lived in wooden huts and their gardens were washed away by the heavy rains. As a result their food dwindled and at the end of the winter approximately 19 men had died.

Charles Bell (1813-1882) painting of Jan van Riebeeck arrives in Table Bay in April 1652www.andrewboraine.com

Land was sighted on 5 April 1652 and the ships docked the next day. Within a week of the arrival of the three ships, work had begun on the Fort of Good Hope. The aim was to establish a refreshment station to supply the crew of the Company's passing trading ships with fresh water, vegetables and fruit, meat and medical assistance. However, the first winter experienced by Van Riebeeck and his crew was extremely harsh, as they lived in wooden huts and their gardens were washed away by the heavy rains. As a result their food dwindled and at the end of the winter approximately 19 men had died.

The arrival of Van Riebeeck marked the beginning of permanent European settlement in the region. Along with the Council of Policy, Van Riebeeck came equipped with a document called the ‘Remonstrantie’, drawn up in the Netherlands in 1649, which was a recommendation on the suitability of the Cape for this VOC project.

Van Riebeeck was under strict instructions not to colonise the region but to build a fort and to erect a flagpole for signaling to ships and boats to escort them into the bay. However, a few months after their arrival in the Cape, the Dutch Republic and England became engaged in a naval war (10 July 1652 to 5 April 1654). This meant that the completion of the fort became urgent. Fort de Goede Hoop – a fort with four corners made of mud, clay and timber – was built in the middle of what is today Adderley Street. Around this a garden was planted and meat was bartered for with the Khoikhoi (who were initially called Goringhaikwa, and later Kaapmans). The construction for Castle of Good Hope which stands today only began in 1666, after Van Riebeeck had left the Cape, and was completed 13 years later.

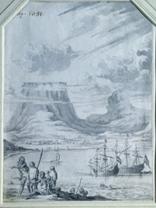

Van Riebeeck’s Original Fort on the Shores of Table Bay, 1658 by Wouter Schouten (1638-1704) . Source: William Fehr Collection. Permission:www.africamediaonline.com

Although the VOC did not originally intend to establish a colony at the Cape, permits were issued in February 1657 to free nine company servants (who became the Free Burghers) to farm along the Liesbeeck River in order to deal with a wheat shortage. They were given as much land as they could cultivate in three years but were forbidden to trade with anyone other than the VOC. With the number of private farms increasing, by 1659 the station was producing enough to supply any passing ship. The station also began to experience a chronic labour shortage and because the Khoisan were seen as ‘uncooperative’, slaves were imported from Batavia (now northern Jakarta) and Madagascar in 1657.

Van Riebeeck’s Original Fort on the Shores of Table Bay, 1658 by Wouter Schouten (1638-1704) . Source: William Fehr Collection. Permission:www.africamediaonline.com

Although the VOC did not originally intend to establish a colony at the Cape, permits were issued in February 1657 to free nine company servants (who became the Free Burghers) to farm along the Liesbeeck River in order to deal with a wheat shortage. They were given as much land as they could cultivate in three years but were forbidden to trade with anyone other than the VOC. With the number of private farms increasing, by 1659 the station was producing enough to supply any passing ship. The station also began to experience a chronic labour shortage and because the Khoisan were seen as ‘uncooperative’, slaves were imported from Batavia (now northern Jakarta) and Madagascar in 1657.

The land on which the Dutch farmed was used by the Khoikhoi and the San, who lived a semi-nomadic culture which included hunting and gathering. Since they did not have a written culture, they had neither written title deeds for their land, nor did they have the bureaucratic framework within which to negotiate the sale or renting of land with strangers from a culture using written records supported by a bureaucratic system of governance. Hence Van Riebeeck, coming as he did from a bureaucratic culture with a unilateral, albeit written, mandate to establish a refreshment station, refused to acknowledge that land ownership could be organised in ways different from the Dutch/European way. He denied the Khoisan rights and title to the land, claiming that there was no written evidence of the true ownership of the land. Consequently in 1659 the Khoikhoi embarked on the first of a series of unsuccessful armed uprisings against the Dutch invasion and appropriation of their land – their resistance would continue for at least 150 years.

In response to the growing skirmishes with the local population, in 1660 Van Riebeeck planted a wild almond hedge to protect his settlement. By the end of the same year, under pressure from the Free Burghers, Van Riebeeck sent the first of many search parties to explore the hinterland. Van Riebeeck remained leader of the Cape until 1662. By the time he left the settlement in May 1662 it had grown to 134 officials, 35 Free Burghers, 15 women, 22 children and 180 slaves.

Statue of Jan van Riebeeck, Adderly Street, Cape Town

The day of Jan Van Riebeeck’s arrival became a public holiday with the 300th anniversary in 1952 and was celebrated as Van Riebeeck’s Day until 1974. During the tercentenary celebration on 6 April 1952, the Joint Planning Council (made up of members from the ANC, SAIC, SACP and COD) held mass meetings and demonstrations throughout the country as part of the lead up to the Defiance Campaign. The ANC and TIC issued a flyer entitled ‘April 6: People Protest Day’.

Statue of Jan van Riebeeck, Adderly Street, Cape Town

The day of Jan Van Riebeeck’s arrival became a public holiday with the 300th anniversary in 1952 and was celebrated as Van Riebeeck’s Day until 1974. During the tercentenary celebration on 6 April 1952, the Joint Planning Council (made up of members from the ANC, SAIC, SACP and COD) held mass meetings and demonstrations throughout the country as part of the lead up to the Defiance Campaign. The ANC and TIC issued a flyer entitled ‘April 6: People Protest Day’.

In 1980 the public holiday was changed to Founder’s Day. The holiday was abolished in 1994 by the democratically elected ANC government. However, statues of Jan van Riebeeck and his wife remain in Adderley Street, Cape Town. The coat of arms of the city of Cape Town is also based on that of the Van Riebeeck family, and Hoërskool Jan van Riebeeck is a popular Afrikaans high school in the centre of Cape Town. Read more on the history of Cape Town.

When Van Riebeeck left The Netherlands in 1651, the Council of Policy, a bureaucratic governing structure for the refreshment station, had already been established. On board the Dromedaris Van Riebeeck conducted meetings with his officials – minutes of the meetings of the Council of Policy, dated from December 1651, have been carefully archived.

Charles Bell (1813-1882) painting of Jan van Riebeeck arrives in Table Bay in April 1652www.andrewboraine.com

Charles Bell (1813-1882) painting of Jan van Riebeeck arrives in Table Bay in April 1652www.andrewboraine.comThe arrival of Van Riebeeck marked the beginning of permanent European settlement in the region. Along with the Council of Policy, Van Riebeeck came equipped with a document called the ‘Remonstrantie’, drawn up in the Netherlands in 1649, which was a recommendation on the suitability of the Cape for this VOC project.

Van Riebeeck was under strict instructions not to colonise the region but to build a fort and to erect a flagpole for signaling to ships and boats to escort them into the bay. However, a few months after their arrival in the Cape, the Dutch Republic and England became engaged in a naval war (10 July 1652 to 5 April 1654). This meant that the completion of the fort became urgent. Fort de Goede Hoop – a fort with four corners made of mud, clay and timber – was built in the middle of what is today Adderley Street. Around this a garden was planted and meat was bartered for with the Khoikhoi (who were initially called Goringhaikwa, and later Kaapmans). The construction for Castle of Good Hope which stands today only began in 1666, after Van Riebeeck had left the Cape, and was completed 13 years later.

Van Riebeeck’s Original Fort on the Shores of Table Bay, 1658 by Wouter Schouten (1638-1704) . Source: William Fehr Collection. Permission:www.africamediaonline.com

Van Riebeeck’s Original Fort on the Shores of Table Bay, 1658 by Wouter Schouten (1638-1704) . Source: William Fehr Collection. Permission:www.africamediaonline.comThe land on which the Dutch farmed was used by the Khoikhoi and the San, who lived a semi-nomadic culture which included hunting and gathering. Since they did not have a written culture, they had neither written title deeds for their land, nor did they have the bureaucratic framework within which to negotiate the sale or renting of land with strangers from a culture using written records supported by a bureaucratic system of governance. Hence Van Riebeeck, coming as he did from a bureaucratic culture with a unilateral, albeit written, mandate to establish a refreshment station, refused to acknowledge that land ownership could be organised in ways different from the Dutch/European way. He denied the Khoisan rights and title to the land, claiming that there was no written evidence of the true ownership of the land. Consequently in 1659 the Khoikhoi embarked on the first of a series of unsuccessful armed uprisings against the Dutch invasion and appropriation of their land – their resistance would continue for at least 150 years.

In response to the growing skirmishes with the local population, in 1660 Van Riebeeck planted a wild almond hedge to protect his settlement. By the end of the same year, under pressure from the Free Burghers, Van Riebeeck sent the first of many search parties to explore the hinterland. Van Riebeeck remained leader of the Cape until 1662. By the time he left the settlement in May 1662 it had grown to 134 officials, 35 Free Burghers, 15 women, 22 children and 180 slaves.

Statue of Jan van Riebeeck, Adderly Street, Cape Town

Statue of Jan van Riebeeck, Adderly Street, Cape TownIn 1980 the public holiday was changed to Founder’s Day. The holiday was abolished in 1994 by the democratically elected ANC government. However, statues of Jan van Riebeeck and his wife remain in Adderley Street, Cape Town. The coat of arms of the city of Cape Town is also based on that of the Van Riebeeck family, and Hoërskool Jan van Riebeeck is a popular Afrikaans high school in the centre of Cape Town. Read more on the history of Cape Town.

References:

• Aartsma, H (2008). ‘Early history of the Cape Colony, South Africa’ from South Africa Tours and Travel [online]. Available from www.south-africa-tours-and-travel.com [Accessed 6 March 2012]

• SouthAfrica.to (date). ‘Jan van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 - 18 January 1677)’ from SouthAfrica.to [online]. Available from www.southafrica.to

• Turton, A. R. (2009). “A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family ”“ Our Story, Part A: Pre-1700” from How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an Africa? [online]. Available from www.anthonyturton.com [Accessed 7 March 2012]

• SouthAfrica.to (date). ‘Jan van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 - 18 January 1677)’ from SouthAfrica.to [online]. Available from www.southafrica.to

• Turton, A. R. (2009). “A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family ”“ Our Story, Part A: Pre-1700” from How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an Africa? [online]. Available from www.anthonyturton.com [Accessed 7 March 2012]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)